Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Pandora | iHeartRadio | Email | TuneIn | Deezer | RSS

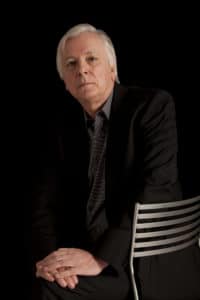

Ep. 21 — A disenchanted doctor finds secret inspiration for his groundbreaking Parkinson’s research from a heroin addict / Dr. Andrew Lees, University College of London, Institute of Neurology.

Dr. Andrew Lees was a young medical student when he realized that his profession was not everything it was cut out to be.

Feeling suffocated by the conservative and powerful British medical system, which gave little room for independent thought and experimentation, Lees was at risk for dropping out.

Then one day, Lees, a Liverpool-born avid Beatles fan saw the cover of their new album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

When Lees scanned the celebrity-laden faces on the album cover, he saw someone he didn’t recognize.

It was William S. Burroughs, the Beat Generation writer, heroin addict, and harsh critic of doctors and the medical establishment.

Feeling quite anti-establishment himself, Lees began reading Burroughs’ work, starting with his most controversial book, “Naked Lunch,” and was soon sucked into Burroughs’ intellectual orbit.

Lees was inspired and influenced by Burroughs’ writings about his frequent self-experimentation with dangerous opiates and his efforts to kick his various drug addictions.

Re-energized, Lees dedicated his career to conduct ground-breaking research into the treatment of Parkinson’s disease, including using the drug Apomorphine to treat advanced complications of the disease — a drug Burroughs had used to kick his heroin addiction.

Lees became one of the world’s most respected and cited neurologists on the disease.

Because of Burroughs’ checkered reputation, Lees kept his “Invisible Mentor,” a deep secret because he was afraid his colleagues would ostracize him.

But late into his distinguished career, Lees finally picked up his courage and told the world about his muse through his book, Mentored by a Madman: The William Burroughs Experiment.

Tanscript

Chitra Ragavan: For much of his celebrated career renowned British neurologist, Dr. Andrew Lees, kept a deep professional secret from his peers and the world. The secret was that his groundbreaking research into Parkinson’s disease was deeply influenced by the controversial American writer and heroin addict, William S. Burroughs. It all began when Dr. Lees, saw a face he didn’t recognize on the cover of the Beatles album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Acting on idle curiosity, Lees learned it was William Burroughs. Pretty soon Lees was going down the Burroughs rabbit hole, learning from a man he would never meet, but who would become his life-long invisible mentor.

Chitra Ragavan: Hello, everyone. I’m Chitra Ragavan, and this is, When it Mattered. This episode is brought to you by Good Story, an advisory firm helping technology startups find their narrative. I’m joined today by Dr. Andrew Lees, Professor of Neurology at University College, London Institute of Neurology. His book about Burroughs is called, Mentored by a Madman: The William Burroughs Experiment. Dr Lees, welcome to the podcast.

Dr. Lees: Thank you, Chitra.

Chitra Ragavan: You achieved global recognition and many, many awards for your work on Parkinson’s disease and abnormal movement disorders and you are one of the most cited researchers in the field. And one could argue that no one should be less afraid of ostracism by your peers than you. What was it about William Burroughs himself and about the culture of the medical profession that made you afraid to disclose his influence on your work and why did you keep it a secret for so long?

Dr. Lees: Well even today, the British medical establishment is very conservative and also very powerful. So that, if you blot your copybook particularly as a trainee, you end up in the Outer Hebrides during something that you don’t really want to do. We were all, I think certainly as trainees quite fearful because unlike the United States which is far bigger, you could move to another hospital or another institution, the number of options available to, for example, a medical resident was quite few. We really watch our Ps and Qs and be very careful if we wanted to get the patronage from seniors. We really needed to advance in our career. If you really wanted to be a neurologist it was highly competitive, and you had to toe the line. Really, there was no room for rebelliousness or anti-establishmentism.

Chitra Ragavan: Burroughs was not a poster child for good behavior.

Dr. Lees: No, I mean, of course most doctors didn’t even know he was in fact, at least the younger doctors. I mean, the people of my own generation, children of the 60s, I mean, most people would know at least about him. They may never have read him that he was involved with the counter culture and the movement of the beats and so on. But later on he was really, I think, largely forgotten and very few doctors would have read him. He wouldn’t be the sort of person that you would recommend to a young person hoping to take up a career in medicine.

Chitra Ragavan: What was it about him? What were his most controversial aspects of his writing and his thinking, just to name a few for those who are not that familiar with his work?

Dr. Lees: Well, when I first read Naked Lunch, I didn’t know whether to vomit or laugh. It’s a mixture of routines almost carnival-like in which well, one intermixes very humorous sketches, particularly, Dr. Benway, the antithesis of a good doctor with sort of urinal lavatory humor involving hanging, which is called… people hanging themselves for what’s called angel lust, to get sexual gratification. Some very lurid homosexual scenes, particularly for the 60s when homosexuality was still illegal both in the States and in the UK.

Dr. Lees: There were some things when I first read Naked Lunch that I really found quite repulsive. And his life of course, was a very difficult one. He was as you mentioned in the introduction, he was a heroin addict. He was a homosexual at a time when homosexuality was illegal and he killed, possibly deliberately or possibly by accident, his common-law wife, Joan Vollmer, in a sort of William Tell kind of drama that he set up in Mexico City in the Bounty Bar.

Dr. Lees: He asked his common-law wife, Joan, to put a glass on the top of her head, and then he fired a gun. And instead of hitting the glass, he was a good shot, he liked firearms and he was a good shooter, but he missed and he killed her with a shot in the forehead. He had a very troubled life and spent 15 years in psychoanalysis in New York City. He wasn’t somebody who you would set up as a paragon of virtue or somebody who really one could imagine ever possibly being a doctor, although he actually did want to be a doctor. And after he’d graduated at Harvard reading American literature, he toyed with the idea of going to medical school.

Dr. Lees: He hadn’t done his graduation in mathematics and science so he wasn’t eligible to go to an American medical school, but he enrolled at the University of Vienna, just before the World War II, but dropped out after one term. It’s not really quite clear why he did drop out. He did have an appendicitis and at first missed some of his classes, but I think he just didn’t enjoy rigid training and apprenticeship which one needs to become a doctor. I mean, even when he was at Harvard, although he graduated, he set up his own curriculum. He didn’t attend too many lectures and didn’t read the books that were recommended by his tutors. He made his own educational system within the bounds of Harvard, which he actually hated. He didn’t like Harvard at all and found it sort of stuffy, conservative, and untruthful and deceitful

Chitra Ragavan: So this is somebody who was very controversial and unconventional and you say in your book that you’ve always had this deep seated fear of authority and you were unhappy in your medical career at the time. What was it that you are most unhappy about towards practicing medicine that when you saw his face on the cover and you looked at his first book, you were so drawn in?

Dr. Lees: Yes. I mean, I think I really became mainly disenchanted with medical studies in my final clinical year. And I wasn’t really sure whether I would be suitable to spend the next 50 years of my life looking after people with serious illnesses. It was a mixture of some of the things I saw on the ward. Some of my teachers were really very good teachers and very influential and inspirational. But there were one or two sort of diva doctors, particularly surgeons who were quite aggressive, quite belligerent, egotistical and hubristic who really didn’t like to give bad news and only really basked in their successes but didn’t want to admit their mistakes. And I think that that kind of prevalent attitude of paternalism, which was endemic in medicine in the 60s and happily is now almost disappeared was one of the things that put me off.

Dr. Lees: I mean, I also when I was doing psychiatry, Burroughs, was particularly interested in psychiatry and psychiatric treatments and read a lot of medical papers, and kept up to date with sort of things like Scientific American. I mean, when I saw how mental patients were being treated with insulin coma, electrical shock, lobotomy and so on. I mean, this seemed quite gruesome and I wasn’t sure really whether it was very effective. The evidence suggesting that these treatments were useful was not very clear. It was things like that which led to disenchantment. Plus of course, it was the swinging 60s counter culture. People were questioning everything conventional. I had a rebellious streak which was a feature actually not just in me but probably of the whole of my generation, the 60s generation.

Dr. Lees: This I think worked a little bit against me. I became sort of contradictory and rebelled against the conformity of British medicine at that time. It got quite serious, I got quite depressed. I needed to take tablets for a few weeks and I seriously considered dropping out. And it was around that time that one of my friends was reading Naked Lunch, and I pinched his copy of the book and started reading it. This was a couple of years after I’d been introduced to William Burroughs on the Sgt. Pepper album. I’d never, I mean, apart from identifying, learning who he was… in fact, I identified every single person on the Sgt. Pepper album.

Dr. Lees: When I got all, I mean, I was born in Liverpool, so I was a great fan of the Beatles. I’ve got their seven first albums before Sgt. Pepper. And of course I rushed out to buy Sgt. Pepper, but I think what was perhaps a little bit different and probably was a clue the time I eventually become a neurologist was I became quite obsessed with the cover. When I first looked at it I could only identify about 30% of the people on the cover. But I managed to get a key from a magazine and look through and identify all the faces with names on the cover and that’s when I first heard of William Burroughs. But I didn’t really get into exploring what he’d written about until a couple of years later during this critical period of disenchantment just before I was due to qualify as a doctor.

Chitra Ragavan: And what did he say in his writings that actually kept you in the field and gave you encouragement to keep moving on with this career?

Dr. Lees: Well, I mean, he spoke to me really through his writings. He told me that I should question everything, and he told me that I shouldn’t be afraid of self-experimentation. And he told me that control systems were there to be broken down. And these were things which I lapped up because of the fact that I was already feeling a little bit like myself based on my own experience, so it spoke to me very much. And then some of his sketch, for example of Dr. Benway, who I’ve mentioned who’s one of his most famous characters and recurs in several of his other books as well as Naked Lunch.

Dr. Lees: I mean, he seemed to remind me in a way of one of my teachers, a very arrogant surgeon, a chest surgeon who would have his patients have lung cancer operation standing up almost to attention in their beds. They had to sit up rigidly straight in the beds and were not allowed to speak to him or ask questions and he just kind of walked around the ward not really giving them any comfort or kindness, and just basking in his competence as a good surgeon. And although Benway, we’re not trying to say that this man was exactly like Benway, there was some resonance between the barbaric things Benway was doing in the name of science and what I was seeing on the ward.

Chitra Ragavan: We have to note here that where Burroughs had the greatest influence on you was in your work as a researcher, but definitely not in your work as a doctor because Burroughs was not a good sort of a role model for doctoring.

Dr. Lees: No, as I said to you he always saw himself as a doctor. And in many of the interviews that people can listen to on YouTube, he often said in the interviews he was very interested in doctoring. And to his group of friends, people like Ginsburg, Jack Kerouac, and the younger people who he tended to cultivate and collect around him, he behaved almost like a shaman to them. He did, I think, always have this feeling that he might’ve been a good doctor, but the reality was that he would have probably been a terrible doctor. I mean, he would have been selective, I think he would have chosen people who interested him and devoted a lot of attention to them at the expense of all the other people who came to see him.

Dr. Lees: He may have done negligent things on them because I think he wouldn’t have followed the Hippocratic Oath and the rules of good doctoring. But I think in that sense he had a very ambivalent and ambiguous relationship with the medical profession. I mean, he had seen huge numbers of psychoanalysts all of which he found completely useless. He felt that they hadn’t helped him at all. He’d been admitted to Bellevue Hospital in New York with an erroneous diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia after he cut one of his fingers off after a row with a boyfriend. And he’d been mislabeled as a schizophrenic by a psychiatrist at the hospital. And then he later on in his life, of course, he met a lot of pusher doctors, doctors working up in the upper East side and the upper West side of New York City, who would give if he behaved nicely he could get a prescription.

Dr. Lees: He always said that patients had to have a good bedside manner in order to get what they want from doctors. He cultivated this air of politeness and kindness in order to get the prescriptions of opioids that he needed. He kind of knew how to manipulate doctors. And then later on in his career, he met one or two doctors which he respected very much like, Dr. John Dent, who treated him for heroin addiction in London with a drug called apomorphine. And he had a great respect for Dent, because Dent understood him and they were able to have a good equal dialogue between the two of them, not as a doctor and a patient but really almost as a friend. And they hit it off and Dent’s treatment really helped him a lot and allowed him to complete Naked Lunch and get it published and finally get some belated recognition for his literary talent.

Chitra Ragavan: You spend the majority of your career focusing on the use and impact of the most effective medicines for treating the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease and Burroughs inspired you to find this groundbreaking treatment for Parkinson’s. How did that come about? And talk a little bit about the disease and this drug and the impact that it had both on the patients and on you and your career.

Dr. Lees: Well, Burroughs took almost every mind-altering drug that’s ever been invented, so he was well ahead of people like Timothy Leary, taking all the psychedelic drugs in the late 50s. And what interested me about him was that he treated his own brain as if it was a Petri dish for growing things. Also, he was very scientific in his way of writing about drugs, particularly for an author who wasn’t a scientist. If you read his descriptions of his self-experimentation with drugs like amphetamine, with opiates and the psychedelic drugs, you can learn a great deal about the actual effect of these drugs. And this self-description spoke very much to me much more than the very dry medical accounts written often by doctors who not had any personal experience of taking mind-altering drugs. It helped me to understand the effect of these drugs.

Dr. Lees: Now, the other thing of course was that he self-experimented. When I was starting my medical research in the late 70s, early 80s at University College Hospital, we were actually encouraged to self-experiment. It seemed as if there was nothing more ethical than if you are trying a new drug for a particular illness. In my case, it was Parkinson’s disease treatment research. Even if you haven’t got Parkinson’s, you should at least take the drug to make sure it was safe, it was tolerated and to know what it was like.

Dr. Lees: In the 80s, which was a period which people look back on now as a period in the United Kingdom of great austerity and control, for me, compared with now it was a period of great freedom because my teachers were encouraging us to self-experiment with drugs. It was part of the protocol. Nowadays, this is very much frowned on and it’s gone underground. You can’t get papers of self-experimentation published in high-impact medical journals. It’s considered to be subjective. It’s of course, not without risks so you’re putting yourself at a certain amount of danger and any equal one studies that means scientific studies carried out on just one person and particularly yourself are really considered not to be of much value now, which I think is a great shame and actually a great mistake.

Dr. Lees: For those two aspects, I think he helped me a lot to record what I felt myself with these drugs and to report the drugs that we were trying. And then one of my greatest achievements in medicine at least from my perspective, it’s not what my peers think is my greatest achievement, but it is what I see as my greatest achievements is the re-introduction of a drug called apomorphine for the treatment of severe Parkinson’s disease. And this drug, interestingly, despite its name is not a narcotic, although it is made from morphine in the laboratory.

Dr. Lees: It was discovered in the 60s that it stimulates dopamine receptors in the brain and Parkinson’s disease in a very simple way is due to a deficiency of dopamine, the brain is not producing enough dopamine. Apomorphine, once it was known that it could stimulate dopamine receptors, was a potential treatment for Parkinson’s disease, although, because it had to be injected, nobody had really taken it very much further. And I remembered Burroughs’ descriptions in Naked Lunch about how he had gone to see John Dent in London when he was desperate.

Dr. Lees: At the end of the line he’d been in Tangiers and I think he’d come to the conclusion that if he went on taking dope, he was going to kill himself pretty quickly. He arrived in London in a pretty desperate state. His parents were well off. His grandfather had invented an adding machine and they were from St. Louis, he was born in St. Louis. He depended very much up until the age of 50 stipends and from his family. His family gave him an allowance and helped him out of all sorts of fixes, probably without that it wouldn’t have happened. Anyway, with their help he arrived in London at Joe Dent’s doorstep.

Dr. Lees: And Dent was one of the few people using apomorphine to treat drug addiction. Now, it had been used earlier as what was thought to be an aversion therapy because apomorphine makes people vomit unless you do something to stop the vomiting with an antidote. And it was thought that it stopped craving in drug addicts and alcoholics by a sort of Pavlovian aversion effect. It made people sick and they if thought they took it with alcohol, they wouldn’t want to take it again.

Dr. Lees: But Dent, even before it was known that apomorphine stimulated dopamine receptors believed it was working as a metabolic stimulant on the back brain. He explained all this to Burroughs, and because Burroughs had an interest in science, he wasn’t scientifically trained but had an interest in science. He liked this idea and it came as quite a refreshing hypothesis compared with the drug dependent doctors that he’d met previously and who would failed to help him. He kind of bought into the idea of what he called, a junk vaccine. And this really helped him.

Dr. Lees: Now, when I started to do my research, I thought, back to Naked Lunch and I remember apomorphine and now knew that apomorphine stimulated dopamine receptors. There was a kind of scientific rationale now of the resurrection of apomorphine for the possible treatment of Parkinson’s disease. I have to thank him also for helping to cue me and perhaps speak to me to say, “Look, why don’t you try apomorphine? Well, why don’t you try apomorphine?” Which I think he did in a way. And that drug of course is now marketed, commercialized and it’s been used to treat thousands of people with late stage Parkinson’s disease, so I have to thank him for that too.

Chitra Ragavan: One of the other things you did in, I think this was late in your career was you kind of followed Burroughs in his footsteps, so to speak. And you went to the Amazon to try to self-experiment with a native vine that he had experimented on and to see what impact that might have on Parkinson’s disease. What was that experience like and what was that vine, and what did you think of that whole research project?

Dr. Lees: Yes. Well, in desperation Burroughs had in the early 50s, Burroughs had read a pulp magazine at Grand Central Station in New York, in which he read about an Indian medicine which the article said had telepathic qualities, which is now known largely as, most people call it the Ayahuasca, which has many different names. And he was very interested in this. He researched it at the New York Public Library and found actually very little because not much was known about it at that time. But he learned that the CIA and the KGB were experimenting with it during the cold war period as a possible truth drug to be used as a type of brainwashing. He was kind of intrigued by this and had ideas about writing an article about this after he explored it himself.

Dr. Lees: He headed off from the States to Colombia. And it was his very good fortune to meet Richard Evans Schultes, who is now regarded as the father of modern ethnobotany, a man who started as a doctor but became so interested in ethnobotany that he switched to botany at Harvard. He was almost a contemporary of Burroughs at Harvard, although they didn’t know one another at that time. And Burroughs, just by chance bumped into Schultes. And Schultes who also himself taking many hallucinogenic drugs during his 10, 15 years traveling through the Amazon agreed to take Burroughs with him and introduced him on their travels to the effect of what Burroughs referred to as under another name called Yage, and published his writings with Alan Ginsburg called the Yage Letters, which was one of the first books I read after Naked Lunch of Burroughs which describes his experiences in the forest.

Dr. Lees: Now, I had this also at the back of my mind and Burroughs reported in the Yage Letters that this drug had broken down a lot of barriers, opened horizons, and altered his concepts of space time. It wasn’t just hallucinations. He did see hallucinations, but it was the time-bending aspects of the drug which particularly intrigued him. He didn’t experience any telepathic effects much to his disappointment. I’d remembered this, and I’d remembered it partly because I also had encountered Richard Schultes before I went to medical school. Because before I went to medical school, I had shared passions. One was science. I had two conflicting passions. One was science and the other was art. And it was only after I’d got into medicine that I found a way of reconciling these two things.

Dr. Lees: And my science interests were really natural history and particularly, botany. I knew about Richard Spruce, who was a Victorian Amazon botanist and who Schultes had written a lot about. And he was also one of Schultes heroes as one of the early planet collectors, so there was all this background. And then in my early 60s, I began to tread water and run out of ideas. I’d had a moderately successful career in medical research. I had written a lot of good papers, but I was really running out of creative new ideas. And I toyed with the idea of retiring, but I was still really curious for new cures. We still haven’t cracked Parkinson’s disease. The best treatments were by this time 40 years old and I wanted to try and keep going.

Dr. Lees: I’m a regular, I have some visiting professor posts in South American universities and I attended a medical conference in Columbia and had the opportunity to go to Leticia, which is in the Amazon jungle, the Colombian Amazon. And I made contact with a shaman called Donna Angelica, who I think was an authentic person. It wasn’t a crummy, touristic kind of experience. And I took my first psychedelic drugs at the age of 62. I’d had the opportunity many times to take LSD as a young man, but I was always terrified of taking it because I didn’t think my mental capacities would stand it. But by the time I got to 62 I felt that my brain was mature enough to get the best out of psychedelics.

Dr. Lees: I plucked up courage and did it. And it was a very positive experience for me, particularly because it brought, I mean as you go on in your medical career and you begin to know more and more about less and less, the system tends to make you very rigid. You know everything in a sense, but you know everything about almost nothing. I think what it helped me to do was really break down barriers, be much more open in my thinking and to look beyond my narrow specialty for new ideas. And I did that and I think it’s been very helpful.

Chitra Ragavan: Looking back on the influence that Burroughs had on your life, what advice would you give new doctors, new neurologists that are just entering the field as to how they should approach their thinking and their research, and their way of understanding diseases and learning how to treat them and dealing with patients and all of that?

Dr. Lees: Well, I would say, first of all, and this is not easy to achieve. I mean, neurology is full of brutal neurodegenerative diseases many of which don’t get as much publicity and medical coverage for example, compared with cancer, HIV, heart disease. We have to give a lot of bad news and we need a lot of compassion. I think that if you don’t question and ask questions and try to be curious to find better ways of answering the difficult questions, our patients ask us and also to look for better treatments, then you do run the risk of being burnt-out. If you, however a good doctor you are, if you’re just seeing patients every day and you’re not having time to question and be curious. The first thing I would say is try to devise your job plan so that you leave a bit of time aside to do research.

Dr. Lees: Now, I’m not talking about working in a laboratory because this is very specialized and you need to devote all your time to working in a wet laboratory. What I’m talking about is trying to pursue questions that we’re asked every day in the clinic and look for answers. And you don’t need high powered technology or massive amounts of money to do that, you can do very valuable research. I would encourage young people to do that. Burroughs used to say, “Nothing is true, everything is committed.” And I think that certainly young doctors should question everything. I always say to them when I’m teaching them, “Look, don’t take anything I’m telling you for granted. Question it, ask me for evidence.” “How do I know?” These sorts of things so that they must become a light unto themselves.

Dr. Lees: And I think to be a good doctor you sometimes have to challenge the system. You have to sometimes break rules and even sometimes break laws. And I think to be a medical scientist, this little bit of medical research, in a way you have to be a kind of anarchist because if you believe that you’re on the right track it’s very likely that nobody else will believe it because you’re breaking new horizons. You have to have the determination to go forward with that. And I think that’s what Burroughs and the beat generation did. They were very courageous, they questioned authority and they broke down a lot of conformist attitudes, which I don’t think were very helpful.

Dr. Lees: For all those things, and then the last thing I think is that I would say that to be a good doctor, you need to be an artist and that we should use scientists to help us find better treatments. But to be a good doctor you’re not a scientist, you’re an artist. We don’t deal in certainties, we deal in balance of probabilities, nothing is certain in medicine. You need to be a good person, you have to put your fellow man in front of yourself, which of course Burroughs actually didn’t do. And that’s why we’ve covered why he wouldn’t have made a particularly a good doctor.

Dr. Lees: But where I think, what I got out of him is that you can… I think many advances in research come from the concatenation of different chance findings. If you have a very broad interest, and if for example, you’re interested in collecting butterflies or rocket science and you can bring your interests from those hobbies into your medical practice, this can be a very fertile source of new research ideas which will take you very much beyond the narrow confines that we work in.

Dr. Lees: Everything in life these days is becoming much more specialized. And professors are terrible, I mean, I am one but we’re very narrow minded. We think we know everything about small bits and that’s what I think Burroughs can teach young people, to open up and be open to new ideas and new suggestions and don’t just dismiss them as rubbish. If a patient comes into my office and says, “Dr. Lees, I ate some squid yesterday and remarkably for the last 10 hours I’ve been almost free from Parkinson’s disease.” Instead of just saying it’s rubbish, think about it and look into it. Of course, you can’t look into everything. I mean, this is impossible, but at least open your mind to the possibility that something that seems really quite wacky could actually have substance behind it.

Chitra Ragavan: One last quick question, which is, once your secret came out and you revealed your secret Invisible Mentor, what was the response from the community, from your peers and your colleagues and your friends?

Dr. Lees: Well, the first people to respond were, I remember very well the first people to respond. The first person to respond was a techie from Silicon Valley who wrote to me and said that my book had actually been very inspirational and it helped him in his work to design new technologies. And then a poet wrote to me and said that my book was going to be a cultural classic. I got very nice early responses but no responses for quite a long time from… and I got some nice reviews in literary magazines. Some people said it was a well-written book and so on. That was kind of nice as an aspiring doctor-writer. But the people I really wanted to hear from were my peers because I’d written the book really in the hope that young people might challenge some of the things where I thought we were going wrong, and the time I get some sympathy from my contemporaries.

Dr. Lees: And I’m sure it’s the same in the States. I mean, medicine is a bit like a brotherhood. We’re very busy people and we tend to mix with our own group, our own peer groups. In the book I say, “Neurologists, you’re a bit like policemen. We mix with our own type.” And of course, partly doctors do that because they don’t want to be grabbed at cocktail parties and so on and asked about health issues. We do tend to stick very much together. I was very anxious and preoccupied that I wouldn’t be ostracized because I’ve always enjoyed being a doctor. I mean, I’ve had my struggles and my ups and downs, but it’s been an enormous honor and a privilege to be a doctor. And I’m so glad that my parents originally edged me in the direction of medicine.

Dr. Lees: And the thought of all my friends and contemporaries in medicine saying I go nuts, that I was wacky was quite terrifying. And I think partly was the reason why I didn’t write this book 20 years earlier, where I think in a sense it might’ve had more effect because I would have still been a very leading, a leader in my field as a highly cited neurologist and people might have perhaps respected and taken more notice it. Anyway, I made it in the end and we did it.

Dr. Lees: Eventually the very last people to contact me were my peers. And I got a very nice review in one of the top neurology journals by a neurologist called Ray Tallis, who also writes books. And then finally, a couple of my direct contemporaries who sympathized with some of the issues that I’d actually brought forward and raised. That came as I can tell you, it was a really a great relief for me in the end. But what I’ve actually enjoyed about writing it is that it’s opened up, not only is it opened up my mind to new ideas for science, but I’ve met some very, with book readings meeting different people. I’ve really met groups of people who I’d never really met before and I’ve greatly appreciated meeting them. A lot of artists, a lot of deadbeats, survivors of the beat generation, all these sorts of people. And that’s been really great fun on a personal note for me to do that.

Chitra Ragavan: That’s wonderful. Well, thank you so much for this fascinating conversation. I really, really enjoyed it.

Dr. Lees: Thanks very much, Chitra.

Chitra Ragavan: Dr. Andrew Lees is Professor of Neurology at University College, London, Institute of Neurology. His book is called, Mentored by a Madman: The William Burroughs Experiment, and I would highly recommend a read. Thank you for listening to When it Mattered. Don’t forget to subscribe on Apple podcasts or your preferred podcast platform. And if you like the show, please rate it five stars, leave a review and do recommend it to your friends, family, and colleagues.

Chitra Ragavan: When it Mattered is a weekly leadership podcast produced by Goodstory, an advisory firm helping technology startups find their narrative. For questions, comments, and transcripts, please visit our website at goodstory.io, or send us an email at podcast@goodstory.io. Our Producer is Jeremy Corr, Founder and CEO of Executive Podcasting Solutions. Our theme song is composed by Jack Yagerline. Join us next week for another edition of When it Mattered. I’ll see you then.